Now, the promised yarn about the guitar I couldn’t give away. This comes with a warning to use your mouse in the correct manner with the wrist elevated and not pivoting on the desktop. Before you read this you may like to see two background posts (No1, No2).

MOUSEBITE gave me hell in the mid-90s. The newspaper group where I worked as an editor and page designer had updated its computers.

We had moved to big Macs for the layout. After working mainly on mouse-less publishing systems for decades I was now clicking intensively.

The habit of resting the heel of my right hand on the desk and pivoting while using the mouse created a little callus.

After a year or so, the impact point had a slight redness and gave an occasional painful twinge.

I would joke about the little "mousebite" but about six months later the inflammation suddenly spread into the wrist and the twinges became bursts of head-splitting pain.

The doctor advised me to wear a wrist brace, which limited my guitar playing and slowed me down a lot at work.

THINGS were pretty bleak as I struggled through each day at work, with every slight wrist movement causing intense pain.

After about three months, I feared the injury would ‘take me out’ from my career in journalism and I could hardly play guitar at all.

We moved into a new house that needed some cleaning up around the yard but the mousebite now stopped any sudden or loadbearing movements.

Painkillers helped me get through work but I couldn’t play the guitar.

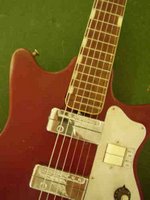

DEPRESSION was the likely cause of a lapse of judgment with my old Eko guitar.

A workmate in his early twenties asked me if I could recommend a guitar brand. He wanted to learn to play.

I said I had a great guitar that he could have. "Just help me move a few logs around my new property, maybe two hours work, and the guitar is yours," I said.

A few days later I asked if he would take up the offer.

"I have to be honest with you, John," he said. "I asked the bloke in the guitar shop about Eko guitars.

"He said they made terrible guitars and not to touch one with a barge pole. I bought a new guitar from him for $500."

Talk about gullible! I offer this 20-something groover a vintage guitar with solid top for virtually nothing and he believes a salesman who tells him not to touch it with a barge pole.

The Eko acoustics do have a special sound, probably because of the thick two-pack finish. The sound is thinner than one would expect from a solid-top guitar but certainly is characteristic of the Eko.

THE wrist pain eventually retreated, and I could play again. Almost a decade later, my old Eko serves me nicely.

A recent innovation was to sand the gloss from the soundboard finish and remove the big plastic scratchplate. This made the tone more even across the range.

Next time the strings are off, I may strip the soundboard back to the timber and just seal it with beeswax.

Such a procedure had a remarkable effect on a similar 1960s high-gloss guitar I had once. That was a Bolero – which a modern guitarshop hero probably would not touch with a barge pole.

The Bolero, with ply soundboard, was marvellous after a stripping and tinkering. Watch out, Eko!